|

皈依佛、皈依法、皈依僧、皈依戒。我想誦一個咒,以憶念我們的皈依處,以便我們的思想能與法相應,而非用私見。

首先,我今天很高興來參加這一種宗教尋求者的法會──尤其這是為妳們這些尋求發展僧伽修行生活的尼僧而舉辦的。

在美國,總有人問我:「需要做和尚或尼僧嗎?是否人人──包括在家人──都可以學戒律?」有時為了不引起對方的排斥,我就籠統的回答,是人人可學得到。

不過,佛鼓勵出家弟子去發展做為僧尼所須具備的覺知力,這不僅由讀誦經典或存正念,也不因我們已披剃搭衣,就可獲得。我們有些人剛開始過出家人的生活時,會覺得有點生疏怪異;我倒是感覺它是自覺的、激勵與熱衷的,這整個感覺是自然而然的。開始的時候,對於如何行事和如何行事如法,我們往往會憂慮,那時它或者會是個負擔。

我們需要忍耐力和幽默感,來適應這種訓練;不要太過壓抑,也不要看得太認真。我想到我的住持同伴阿瑪若法師,在阿姜查的訓練下,他久欲求受大戒;終於在穿上衣袍的第一天,他出外去托缽,這很有沙門的形象。但搭衣使他不自在,特別是在雨天,他的衣袍滑落時。他一會兒要放下缽去拿傘,一會兒又放下傘去提衣;等再抬頭看時,所有的比丘都已走了。在乞食的第一天,他就在村子裡迷了路,又不會說泰語;這時他一切的沙門希望和壯志都被打倒了!他想自己已犯了大錯。現在回顧,他覺得很可笑;不過這可說明:這種沙彌、沙彌尼、比丘、比丘尼的培訓,需要耐心,點點滴滴的去累積經驗。

出家和在家最大的不同,是出家人必須在所面對的境界中修行;而在家人會選擇所偏好,又可以掌控的環境去做。部份──實際上是絕大部份,僧尼要做的,就是放下那種掌控。我們願意處於自己所依存的寺院、師父或環境的鍛鍊境界中。再者,世界的走勢是要金錢、權利、知識和影響力;我們則給自己機會,去放下得到個人權利或地位的希冀或欲望。

我做比丘卅多年了,有次犯了戒,阿姜查要我懺悔一段時期,它比戒律上要求的作法懺還嚴格得多多。我所能做的,便是投入這調鍊,歸順於阿姜查。我做這作法懺兩年多,雖然時間真長,我還是做了──其實是他命令我做的,我必須放棄自己的揀擇。那是很苦又很挑戰的一段時期,我必須戮力鍛鍊自己。一年後,我的心得是:我終於明白了老師的用心。

阿姜查和任何善知識會做的,是願意把我們逼到極點。這是寺院鍛鍊的重點之一:逼我們到事情的極致。我們不是要自我吹噓或要表現不脆弱,不過我們在捉摸探究那些極限、和我們的執取。學習不被我們的極限所困阨,這是很有趣的一種自我挑戰。

當我覺得時間差不多時,我向阿姜查要求不用再做這個懺悔,阿姜查只是看著我,我感覺自己好像被一眼看透似的。

當阿瑪若法師提議我們的寺院名「無畏」時,我對「無畏」這內涵很有興趣;因為怕,我們對任何難事或放下就會退縮。在這冶煉中,我們受挑戰要和畏懼共存並超越它,它不是外在的恐怖,而是一種不舒適和無依恃。

做為出家人,我們有機會面對更多的「不可能」,而用作意和努力去承擔。比如,阿姜查在泰國時,曾經要我們大家把所有的衣搭上,在戒壇裏打坐。他緊閉那棟錫屋頂建築物的所有窗戶,每個人打坐時都在想:「究竟要坐到什麼時候?」但只要我們打瞌睡或昏沉,他就不放大家出去;直到大多數人都打起精神,他才放人。那是一段增長修行信心的艱苦過程。這類情形,其實不一定是障礙,但的確是既不舒服也不愉快。

阿姜查還做一件事,對西方人比較容易,但對泰國人卻很難--在寒冷的黎明時分,做完早課後,他要我們脫下袈裟,在這寒冬裏,只披一塊布橫過胸部。對我這個在加拿大長大的人而言,還算可以鬆口氣;但這對泰國人來說就不同了,我可聽見他們冷得全身打顫。

天氣是外在的,還容易認識和應付;但內心翻騰於兩個極端的境界之間,可就有苦受了。在兩極的關卡處,我們要挺立把持住:我要什麼、不要什麼?同意什麼、否決什麼?接受什麼、不接受什麼?

冶煉出家人,戒律是首要的,其他涵蓋的道德,尚有感官張力的道德(眼、耳、鼻、舌、身、意)、正念資糧的道德(飲食、醫藥、臥具、衣袍)、正命的道德(值得受供,而非諂媚、攀緣施主或用占卜、星術而得)。我們也學習在這些方面守持戒律。戒律有輕重,又有威儀戒與和合戒。然而很有可能,你在守戒相的當口,仍然疏忽地漏失於六識;譬如,用眼、耳向外馳求。

阿姜查訓練的重點,其中有一個我很受用的是:所有規矩、冶煉,是為了明白自己的意圖、欲求──亦即每個起心動念的根源。我們造作的業,是因心中欲求,由心動、行動而導致因果;所以洞悉意圖,就是明白造作,這才能使自己莫再造新業。我們要深究心行錯綜複雜的造作;戒律和我們所受的冶煉,直截的用意,是對欲求之作意和覺知。這樣,可發展心靈的清明。

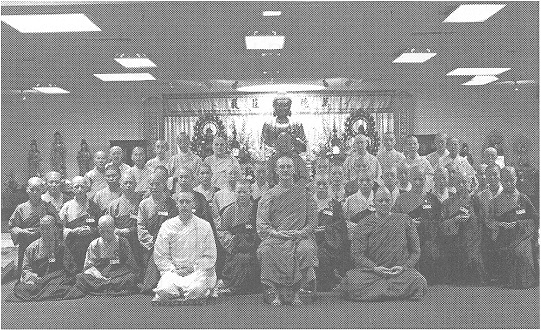

這種訓練,要我們專注在自己的身、口、意,以及生活在團體中。很多人想出家,是因為師父的啟發、想開悟,或欲救度眾生,但我認識的多數人,並不清楚地認識到:出家的訓練,是在生活的互動中。應該要明白這點:僧團是皈依處。從佛解脫、成佛那天起,僧團成立了,僧團即是一個捨棄之乘。

僧團生活並不抽象,它是關於相處交融、互助、分享、彼此容忍、善巧勸諫你的同修和旁人之道。在某方面來說,這些比打坐還更難應付,我們需要很有心的努力去發展此中的藝術。利生之願易發,卻往往忘了就在身旁的他。我們有個師兄弟說:排班在自己身旁的人,就代表了世間苦的十之八、九。

待續

|

|

Homage to the Buddha, Dharma, Sangha, and Vinaya. I’d like to recite a mantra that lets us recollect our refuge so that our perspective is not a personal one but one based on the Buddhadharma.

First of all, let me express my delight in joining you today among an assembly of religious seekers, particularly those seeking to develop a practice in monastic form.

When in America, I am always asked, “Is it necessary to be a monk or a nun? Is the vinaya accessible to everybody, including laypeople?” To not offend people, sometimes I would give a sweeping answer about how it is available to everyone.

But the Buddha encouraged us monastics to develop our perception as monks and nuns, not just from reading and memorizing sutras or being mindful, and not just because we have shaved heads and wear robes. For some of us who first began this lifestyle, it felt strange and awkward. I felt self-conscious, inspired, and enthusiastic. This whole range of feelings is natural. At the beginning, we usually are worried about how to do things and how to do things right. It’s a burden at times.

Patience and humor are needed for us to fit into this training. Don’t be overwhelmed and don’t take certain things too seriously sometimes. One thing comes to mind about my co-Abbot, Ajahn Amaro. When he was training under Ajahn Chah, he had been aspired to become ordained for a long time and on the actual and first day that he got to wear the brown robes, he went out for alms. This fit his image of a sramana [Buddhist monk]. But he was uncomfortable in his robes, especially with the rain and his robes slipping. He had to set his bowl down to get his umbrella, set his umbrella down to pull up his robes. By the time he looked up, all the monks had gone. He was lost in a village where he did not speak any of its language on that first day of his alms round. All of his hopes and aspirations were dashed. He thought he had made a very big mistake. It’s funny now that he looks back. But this tells us that a novice, Bhikshu or Bhikshuni’s training requires patience as one learns bit by bit.

The biggest difference between a left-home person and a layperson is that a left-home person has to practice in any circumstance one finds oneself in. A layperson will find circumstances that he or she prefers, has control over. Part of, actually a lot of, what a monk or a nun does is having to relinquish that kind of control. We are willing to be in situations of training where we are dependent on the community, the teacher or the circumstances. Furthermore, it’s the tendency of the world to acquire money, power, knowledge, and influence. We give ourselves the opportunity to relinquish our wish and desire for personal control, for positions.

I have been a monk for more than 30 years and once I had made a transgression in the vinaya. Ajahn Chah made me do a period of penitence that did not accord with the vinaya. The penitence was much more severe and way more than what the vinaya required. All I could do was to give myself to the training, to Ajahn Chah. I did the penitence for more than two years, which is a very long time; but I did it. Actually, he made me do it. I had to relinquish my own preferences. It was a difficult time that was very challenging. I had to work very hard on the practice. After one year, I had this insight: I actually understood what he was trying to do.

What Ajahn Chah did and what any good teacher will do is being willing to push us to the limit. This is one of the elements in the monastic training: pushing up against the edge of things. We are not being egotistical or promoting a feeling of invulnerability, but we are exploring limitations, our clinging and grasping. This is an interesting way of challenging ourselves while learning not to be restricted by our limitations.

When I felt the time was right, I asked Ajahn Chah to release me from my penitence. All he did was look at me. I just felt transparent.

When Ajahn Amaro proposed the name Abhayagiri for our monastery, I was very interested in the name, in this quality of fearlessness. Because of fear we pull back from letting go, from hard things. In this training, we are challenged to work with and step beyond fear. This fear is not some external terror but a discomfort and insecurity.

As monastics, we have the opportunity to look at things that are impossible and take them on with intention or effort. In Thailand, for example, Ajahn Chah would have us put on all our robes and make us meditate in our old precept platform. He had all the windows closed to this tin-roofed building. We often wondered, “When will this end?” He didn’t let us go if we were drowsy or dozing off. Only when enough people got enough energy going would he release us. Those were awful times that gave us confidence. Situations such as these don’t have to be obstacles, though they’re not comfortable or pleasant.

Another thing that Ajahn Chah did that was easier for westerners but more difficult for the Thai: after the morning chanting or meditation, during the cold before dawn, he had us take off our robes and lay a single piece of cloth across our chest in the very cold of winter. It was a nice break for me since I grew up in Canada, but it was different for the Thais. I could hear them shiver.

The weather is external and easier to recognize and work with, but the mind that flips and flops between extremes leaves a trail of suffering. We need to push up against the extremes: what we want and what we don’t want, what we approve of and what we don’t approve of, what we accept and what we don’t accept.

Precepts is one of the first areas that we recognize as a part of our training. Other virtues include the virtue of sensuous strength (eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind), the virtue of being mindful of the requisites (food, medicine, bedding, robes) and the virtue of livelihood (being worthy of offerings rather than cajoling, developing schisms among donors and using astrology). We learn to follow and apply the precepts in these virtues too. There are major and minor precepts, precepts of comportment and communal harmony. And yet it’s possible to follow the precepts to the letter and still be heedlessly caught up in the senses, such as looking out at the world with our eyes and ears.

One of Ajahn Chah’s emphases and one that I found helpful was that the purpose of all rules and training is to understand intention, volition, the nature of each thought. Karma is created through volition, which is movement toward action that leads to cause and effect. Therefore, to see intention is to understand action. We then disentangle ourselves from creating karma. We investigate the movement of the mind with all actions and complications. The straightforward purpose of the vinaya and our training is about attention and awareness on volition (Sanskrit: cetana). It develops clarity in the heart.

This training is one in which we focus on our own body, mouth and mind, also on living in community. Many are inspired to leave the home-life because they are inspired by the teacher, the wish for enlightenment, or the desire to save all beings; but most people I know don’t recognize clearly that this training is about living with one another. That needs to be made clear. The Sangha is a refuge. Starting the day of Buddha’s liberation, the day of his enlightenment, he established the Sangha. The Sangha is a vehicle for relinquishment.

Living in community is not an abstract principle, it’s about getting along, helping each other, sharing, being patient with each other, admonishing each other skillfully and others. In certain ways, all these are more challenging than meditating. We need to make a very conscious effort to develop these skills. Sometimes it’s easy to think about helping all beings but not the one next to us. One of the monks in our community said: the person next to you in line is responsible for 80 to 90% of the world’s suffering.

To be continued

|