|

當然,我們人都是事後才學得聰明。我花了很長一段時間,才湊合了那年夏天所發生的片片斷斷,而明白這些教訓。這一直就是我們受教於上人的方式──教訓會先來到,而十分頻繁地,在因明瞭而啞口無言的當口,無可爭辯的事實就隨後呈現了。

就像1968年,當我們五人要前往臺灣去受具足戒前,我們排隊向上人告假。我們一齊向他頂禮,但出乎意料之外,上人也要我們互相禮拜。上人做指揮,叫我們後面四個向排第一位的沙彌頂禮;接著我們後面三個,向前面兩位沙彌頂禮;再來我們兩個沙彌尼,向前三位沙彌頂禮;最後,掛尾巴的我,向前面四位頂禮。當我們頂禮時,上人一直是輕鬆而帶著笑容在指引著我們。我記得清清楚楚,上人經過我身邊時,用輕得幾乎聽不到的聲音說:「最後一個,就是第一個!」當時我聯想到上人禪七時的安排,跑香是繞圓圈的,所以沒有哪一個真的是第一或最後──我認為這是我可以終身奉行的教訓。

大約十五年後,當天我禮拜的那四位,都因各種緣故,決定還俗。上人說的那句話,就具有另一層意義──但在說的當天,我是絕對無法領會其義。

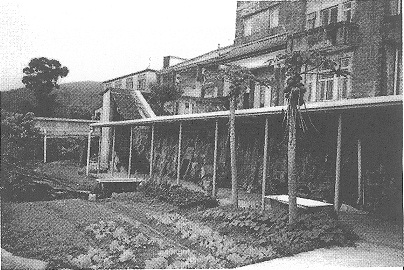

總之,故事發生在八○年代初「那個夏天」;之前的春天,實在美極了!明媚的陽光,使得天氣好得出奇:午後輕風徐來、十日一小雨、夜間月色清涼。當我坐在萬佛聖城園區最東南方那棟建築物的辦公室內,聽著小溪奔流在鵝卵石之間的潺潺流水聲,我決心在此闢一塊菜園;除了我自己,沒人知道我這個主意。或許當時我是這麼認為的,而今回首,看法就不同了!

當我在收集樹枝碎石、清理我選中的私人菜園地時,我該接到的第一個線索就到了。有位比丘尼正好路過,她是知客師;其執事在某種程度上說,也兼做上人侍者,但當時我可沒留意這層關係。她開始與我閒談起來,我以為只是出自她的好奇,她問:「妳要開闢菜園啊?」

我很自信地答:「是啊!」「哦?我們真需要另外一塊菜園嗎?」她輕輕地說,彷彿是自問。「已經有兩大塊公共菜園了,而且人手都不足!」她用同樣輕柔的聲音指明。我點頭,卻繼續工作而沒吭氣。

頓了頓,她稍稍加重語氣,建議:「妳可以去那些菜園幫忙,用不著另開一塊吧!」我保持沉默而沒答腔,忙著做我自己攬的這份工作。最後她點點頭,留下我一個,走開了。我沒有把這個閒談放在心上,事後久久我才想到,很可能當時是上人要她來告訴我:還有更好的選擇,而不說穿是上人的意思。

一兩天後,我向辦公室借了台大型耕土機來翻土。高坐其上,掌控著這麼重的大機器,我確定,我當時相當自豪。但那自豪感很快被摧毀,因為硬鐵犁打到土中的一條蛇,無情地削掉牠背上的肉;我轉身看著牠暴露在朝陽下,在劇痛中發狂般地捲曲抖動,我驚出了一身冷汗。

可是我還繼續開,翻第二道土時,一隻青蛙正巧跳進鐵犁的耕道,被我打個正著,登時一命嗚呼。雙手顫抖的我換下慢檔,試著把這台劊子手機器慢下來──這可是我操作的啊!不管怎樣,我還是將土地給翻好。

不久之後,我在佛殿裡,在上人和大眾前,懺悔我害的這兩條命。上人帶著幾分驚惶的口氣重複:「一條蛇和一隻蛙?」之後,用幾乎是很勉強和傷感的聲音說:「哦!」

我已被訓練來做翻譯;翻譯是我的主要工作──或許應該說:一直都是!當時佛經的英文書極少;上人希望更多譯書能夠出版,而且越快越好。我已有指定的工作,也了解該跟上進度,以便能及時交給「佛經翻譯委員會」負責下一階段的小組。

可是我的菜園計劃,最後變成費時的工作,尤其因為它不是一塊「公家」的菜園;所謂「公家」,言其聖城常住會輪流來照顧此公共菜園,而非我開闢的那塊。我奮力照顧自己的菜園,只有一位老僧尼做幫手;她的鄉音沒人懂,所以大概也不知道哪一塊是公共菜園,便過來幫我忙。如今回首,我意識到:當時她一定以為她做對了事,正如我說服自己種得對一般。菜園茂盛了,我的驕傲也與日俱增。

因為日子總在忙著種植、疏苗、拔草、施肥、澆水及後來的收成,我開始感覺有壓力,便試著晚間來做翻譯。

我們念完咒心後,我就逕直走到東南那棟建築物去;隨手打開幾盞燈,看清走到辦公室的路,就開始開夜車。本該十點半熄燈,但我往往破「宵禁」之規而挑燈夜戰。有一天,上人在他的課上(他在聖城上的課,每個人都會跑去聽)公開地對大眾數落,有人浪費電和愛表現。他是在講我!他明指我就是要引他注意,從遠遠之處來顯示自己也在熬夜工作,是多精進的翻譯者。他埋怨我不知節儉,一個人用一棟大樓,開那麼多燈!他居住和課室所在的那棟樓,可以直視我工作的那棟建築;晚上刺眼的燈光,會打擾到他。上人埋怨之時,我那執著的自我,就悄悄地反駁:「這太誇張了吧!我只開門廊燈照路,到辦公室開了燈後,就回來把門廊燈關了。我壓根兒沒想到晚上去翻譯時,上人會看見燈光。我太忙於工作了!」自我在內心不斷的交戰,使我完全忽略了上人長篇大論裏的含意。總之,那節課結束前,上人宣佈:東南那棟建築物,晚間「限制使用」。而自己的我相心還一直在舔平那傷口。

夏天很快就過了,我忙著顧那快熟的莊稼、忙著除那頑強的野草、忙著準備那即將到來的豐收。翻譯工作雖給拖下去,我的自豪感,卻在第一批青菜收成時膨脹起來。就在那時,那位比丘尼又來了;這次她走得更形慎重──不只是經過,而是衝著我直直走來。她語氣堅定地說:「我來傳上人話給你。」我站立靜候。「他要我告訴妳,這菜園裡收的菜,他一顆也不吃!」

噢!當然啦!我所摘的第一批甜豌豆和嫩青菜,就是想要孝敬師父。她只那麼一句,一點笑容都沒,一聲鼓勵都沒,就傳這尖銳的訊息!

不僅如此,當收成期到來,還造成了大爆滿;大廚房是菜滿為患──菜多到超過夠吃和儲藏的數量。反思之下,我懷疑那多餘之數,可能正等於我那私心田地的收穫。

我花了好長的時間,才把整個事件徹底消化掉;但事後,我非常清楚地發現:我那以「自我」為基礎的菜園案件,已讓上人花了多少寶貴時間和精神,來為我上這一開始我就該明白的一課。

1.於團體工作,和合同作;不要製造以自我為中心的事件。

2.堅持己見,已令我造出一些重業。

3.受何訓練、做何事,謹守承諾,剋期完工。

4.做任何工作期間,絕不自我炫耀,或標異現奇。

5.最痛苦者,自大之果報,既不足養身,也不足養性。

6.結語──雖則最後,卻非最微之義:與大眾一起工作,可產生溫馴的韻律與和諧,而帶來工作本身所給予的福報;還具有泯滅執著之我相的成效。

|

|

Of course we are always wiser after the fact. It took me a long time to piece the lessons from that summer together. That’s how it was, being taught by the Master. The lessons came first. All too often the undeniable truth of them came later in some moment of dumbfounded clarity. Of course we are always wiser after the fact. It took me a long time to piece the lessons from that summer together. That’s how it was, being taught by the Master. The lessons came first. All too often the undeniable truth of them came later in some moment of dumbfounded clarity.

Like the time in l968 when the five of us were lined up for our last bows to the Master before we headed for Taiwan to become fully-ordained monks and nuns. We bowed in unison to him, but then the Master surprised us by having us bow to each other. He directed it, telling the latter four of us to bow to the monk first in our line. Then three of us bowed to the first two monks. We two nuns bowed to the three monks, and finally, I, being last in line, bowed to the four in front of me. The Master kept it light, smiling and giving instruction as we bowed. I remember distinctly him saying in passing, almost under his breath to me, “Last one is first one.” At the time, I connected the comment with the Master’s observations during meditation sessions about how we walked in a circle, so that no one was really first or last. And I thought it a nice lesson to carry with me.

It was some fifteen years later, when the other four whom I had bowed to on that day had, for whatever reasons, decided not to be monastics any more, that the comment took on another meaning—one I could never have grasped on the day it was spoken.

Anyway, the spring of this particular summer in the early ‘80’s was exquisite. Perfect weather prevailed with sunny days, slight breezes in the afternoons, a good rain every ten days or so, and cool moonlit nights. As I sat in my office in the building on the southeastern-most portion of the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas (CTTB) campus, listening to the chattering flow of the creek water as it raced over and between the smooth rocks, I decided to grow a garden. Nobody knew about my decision but me. Or so I thought at the time. In retrospect, I see that differently.

The first clue I should have picked up on came as I was gathering sticks and other debris, clearing the plot of ground I had chosen for the site of my garden. One of the nuns happened by. She was the guest prefect and, as part of that duty, was also the Master’s attendant in some ways. But I did not make that connection then. She struck up a gentle conversation that I assumed was just an expression of her own curiosity. “Are you starting a garden?” she asked.

“Yes,” I replied confidently.

“Oh. Do we really need another garden?” she said softly, almost as if wondering aloud. “There are two large community gardens already started—and we are shorthanded,” she pointed out in the same soft tone.

I nodded, but kept on working and made no comment.

After a pause, she suggested—a little more pointedly, “You could help with those gardens, instead of starting yet another one.”

I remained silent and unresponsive, busy with my self-appointed task.

Finally she nodded and walked on, leaving me alone again.

I did not dwell on the conversation. It only came to me much later that she most likely had been sent by the Master to try to point out to me a better choice than the one I was making, without letting it sound like the Master’s idea.

A day or so later, I had borrowed the large tractor and plow from the office and was breaking ground with the first pass of the plow. Seated so high and in command of that heavy equipment, I am sure I felt more than a little proud. That self-satisfaction got marred quite soon, however, when the hard steel of the plow struck a snake, cruelly stripping the flesh off its back. I turned in my seat and saw it writhing in the morning sun—exposed, distraught, and most likely in agony. I broke out in a cold sweat.

But I kept going. On the second pass through the field, I flushed a frog that hopped right into the path of the plow and died instantly from the blow. My hands trembled as I down-shifted and tried to slow the course of that murderous machinery—manned by me. Nonetheless, I completed the job.

Soon after that, I repented of those two deaths, in the Buddhahall, before the Master and the great assembly. “A snake and a frog?” the Master repeated with a bit of dismay, followed by a rather reluctant and sad-sounding, “Oh.”

I had been trained to translate. It was my main job—or should have been. So few of the Buddhist sutras were in English back then and the Master wanted more of them published as soon as possible. I had my assignment and knew I should keep pace with my work, so that I could pass it on to the next committee of the Buddhist Text Translation Society in a timely fashion.

But my garden project turned out to be time-consuming, especially because it was not an ‘official’ garden. That means the other residents at CTTB took turns working in the community gardens, not the one I had made. I struggled to maintain my own garden, with only one elder nun, who spoke a dialect that no one on campus could really understand and so probably never figured out where the actual community gardens where, coming by to help me. Looking back, I realize she probably figured she was doing the right thing, as I had convinced myself I was. My pride grew as the garden flourished.

Because the days were filled with planting, thinning, weeding, fertilizing, watering, and later with harvesting, I began to feel pressure that lead me to try to work on translation at night.

After we finished the evening mantras, I would walk clear back to that southeastern building, flip on some lights to find my way to my office, and then burn the midnight oil. Lights out was at 10:30 p.m., but I often broke the curfew and stayed up working. Then one day the Master began to grumble publicly during one of his classes (which everyone on campus attended) about wasting electricity and showing off. He was talking about me! He professed that I was just trying to attract his attention, displaying from afar that I was such a diligent translator that I worked at night, too. And he complained about the lack of thrift—one person working in such a big building and turning on so many lights. His residence and classroom was in a building that had a direct line of vision to the building where I worked. The glare of the lights at night, he said, disturbed him. While the Master complained, my tenacious ego silently countered his complaints in my mind. “That’s an exaggeration! I only turn on the porch light until I get the office light on and then go back to turn the porch light off. I never thought about the Master seeing my lights when I went to translate at night. I was too busy working!” My ego made so much racket in my head that I totally missed the message in the Master’s tirade. Anyway, by the end of that class, the Master had declared the southeastern building ‘off limits’ at night. And my ego kept licking its wounds.

Summer passed quickly, and I raced to keep up with the demands of the ripening crops, the stubborn weeds, and the coming harvest. Translation suffered and my pride swelled as I began to gather the first greens. Just about then, that same nun came by. She walked more deliberately this time—not just passing by, but heading directly for me. “I have come to deliver a message from the Master,” she said firmly. I stood silent, waiting.

“He wants me to tell you that he will not eat a single vegetable from this garden.”

Ouch! Of course, I had been gathering those first sweet peas and tender greens with my teacher in mind. That was all she said. No smile. No encouraging word. Just that pointed message.

Not only that, but as harvest time became full-blown, the community kitchen was inundated with garden vegetables—more than could be comfortably eaten or preserved. In retrospect, I suspect the amount of extras probably equaled just about the amount I reaped from my selfish-centered plot.

It took time for me to assimilate it all, but afterwards I saw so clearly how my ego-based garden project had caused the Master to spend his valuable time and energy trying to teach me lessons that I should have known from the start.

1. Join the harmony of community work, do not create an ego-centered project.

2. Insisting on my own way caused me to create some serious karma.

3. Do the job I was trained to do and keep my commitments and meet the deadlines.

4. But while doing any job, do not show off or display a special style.

5. And painfully, the fruits of the ego are unworthy of nurturing the body and go counter to nurturing the spirit.

6. Finally, last but by no means least, sharing in community work generates a gentle rhythm and harmony and brings its own rewards, not the least of which is diminishing the tenacious ego.

|