|

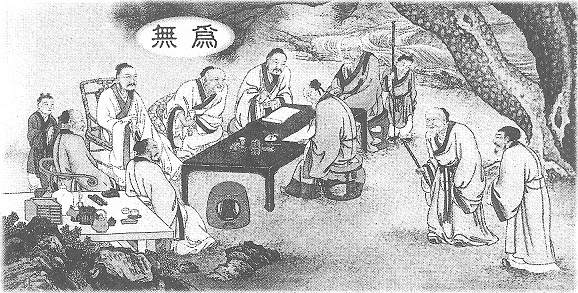

老子姓李,名耳,字聃。春秋楚國苦縣人。曾為周室守藏吏。提倡無為,輕視有為。故曰:「大道廢,有仁義;智慧出,有大偽;六親不和,有孝慈;國家昏亂,有忠臣。」在政治提倡小國寡民。「鄰國相望,雞犬之聲相聞,民至老死,不相往來。」在教育提倡清心寡欲,恢復自然。後因周室衰微,於是騎青牛西出函谷關,為關令尹喜所請,留五千言之道德經。上卷言道:「道可道,非常道。」下卷言德:「上德不德,是以有德。」故稱道德經。出關後,不知所終。後人尊為道教之始祖。

中國先有道教,繼有儒教,後有佛教。雖然佛教是最後才由印度傳進來的,但在這之前傳播的道教及儒教,可說都是在為佛教的東來而開荒舖路、奠定基礎的。道教的始祖老子,其實就是佛教裡的迦葉祖師,孔子則是水月童子轉世,他們看中國的大乘根器即將成熟,所以就發願先到中國來宣揚道教及儒教,以利佛教的東傳。這三者中,儒教猶如小學,道教猶如中學,佛教則是大學。

老子姓李,名耳,字伯陽,諡聃,春秋時代楚國苦縣人,曾經作過東周的守藏吏,是當時的一位大哲學家。他提倡「無為」,輕視「有為」。無為並不是像木偶土人一樣,什麼都不做,而是「為無為而無所不為」。以無為的心,去做一切該做的事,但功成後不居功,不執著於有所為,而攝有為歸於無為,故能無所不為。若是執著於有為,便祇能為小為,而不能成大為了。無為是有為之體、之母,是至神、至妙的。

孔子有次前去拜見老子,和他討論仁義。老子說:「海鷗不是因天天洗澡才白的,烏鴉也不是因天天染黑才黑的。牠們的黑白都是出自天然的本質,所以不能說白就比黑好。你現在用仁義去分辨善惡,在懂得大道的人看來,你所犯的錯誤,就像是強去分別黑白的好壞一樣。」孔子回去以後,三天都沒有說話。他的弟子忍不住問他:「老師,你去見老耳時,你教導了他些什麼?」孔子說:「我看見龍了!龍順著陰陽變化無窮。我祇能張著嘴吧,震驚得一句話也說不出來,那裡還談得上教導他呢?」孔子認為老子已得自然之道,變化無方。

面對一個得道的人,任何的語言都是多餘的、不必要的。若是再執著於後天有形、有質的道理,又如何能窺視龍的一鱗、一爪呢?

所以老子主張:「大道廢,有仁義;智慧出,有大偽;六親不和,有孝慈;國家昏亂,有忠臣。」太古盛世,三皇在位時,以道治天下,萬民一體,將道融入、應用到日常生活倫理中,人人各行其份,故不用提「仁義」大名,而仁義已立。可是後來的君主,不能以道治天下,不修無為的德化,所以大道遂漸隱沒。這並不是大道捨棄人,而是人捨棄了大道,故不得不立「仁義」之名來教化人心。

「仁義」之名立後,若不用智慧來輔助、疏導,則仁不能周遍,義不能廣大,所以智慧就出現了。智慧既出現,天下的人民便偏重於取巧。漸漸地,淳樸的風氣就喪失了。百姓養成虛偽、作假的習慣後,國家民族就逐漸現出衰亡的現象,所以有春秋之亂及五霸之危。這期間雖也有所謂聰明奇智的人士出現,但都是假仁假義,好名尚利,多行詭詐之謀,以圖利自己,這都是智慧出現的害處。

在六親不和時,還能對父母盡孝、對兄弟仁愛,這是困難的。若真有人能如此,則這種「孝、慈」之名,就會傳播開來,令天下人皆知。譬如舜的父親既瞎且聾,又頑固不靈,舜的後母及弟弟又一天到晚想謀害舜,來奪取財產;但舜仍然對父母十分孝順,對弟弟也很友愛。他們可以說是成就了舜的大孝。

在國君昏庸,國家危亂時,一般的臣民但求自保,以至臣節難立、忠義難盡。這時若能捨身報國,力扶大義、鎮安社稷,雖沒有心立志,而「忠臣」之名,自然顯彰。

在政治方面,老子提倡「小國寡民」。所謂「鄰國相望,雞犬之聲相聞,民至老死,不相往來。」人民各安於儉樸,共處於清靜,安其所居、樂其習俗,不好高騖遠、喜新好奇,也不喜向遠處遷徙;這樣,雖有舟車,也沒有用了。鄰國之間,雖然互相看得見,雞犬之聲,也互相聽得到,但人民老死也不相往來。既沒有一切的交涉,自然就不會有戰爭;雖有甲兵,也沒有地方陳列了。

這「老死不相往來」,並非囿居一隅、坐井觀天的「畫地自限」,而是一種高層次的進化。此時,人人能盡心知性,萬物皆備於我身;浩氣充塞於天地之間,道心瀰漫於六合以外。神遊太虛,不行而至,不疾而速;看天地中的一切,如在掌中。這時已沒有天、人的界限,人間就是天上。但這種進化是自然漸進的,若不得其時而貿然去行,必招大亂子。按序漸進,起手也得幾百年;至進化究竟,非千餘年不可。老子的主張是很高尚的。

在教育上,老子提倡清心寡欲。由去除私心入手,再漸漸減少人的欲望,以達到恢復自然天性的目的。

後因東周王室逐漸式微,老子就騎著青牛,西出函谷關。受守令尹喜所請,在臨出關前留下五千言的《道德經》。上卷討論道:「道可道,非常道。」凡是可以用語言說出來的道,都不是真常不壞的道。下卷討論德:「上德不德,所以有德。」有上德的人,絕不會自以為有德,這才是真正的有德行。上、下卷合起來,就稱為《道德經》。老子出函谷關後,從此就再沒有人看過他,也不知道他去了那裡。他可說是道德的開始,存神過化,無始無終,一大至人也。後人尊稱他為道教的始祖。

待續 |

|

Essay:

Laozi’s surname was Li. His first name was Er, and he was also known as Ran. He was born in the Ku County of the state of Chu during the Spring and Autumn Era. He served as an imperial librarian in the Zhou Dynasty and advocated unconditioned, effortless action. He scorned conditioned actions. Hence, he said, “When people abandon the Great Way, they choose to honor the teachings of kindness and righteousness. When intelligence prevails, hypocrisy appears. When there is disharmony in the family, filial piety and kindness appear. When chaos is rampant in a nation, loyal ministers emerge.” In government, he favored small states where “the people of neighboring states can see each other and hear each other’s dogs and chickens; however, they never visit one another until they are old or about to die.” Regarding education, he advocated purifying the mind and diminishing wanton desires in order to return to the nature. He later rode a blue ox westwards, passing through the Hangu Pass [one of the many outposts along the Great Wall]. At the request of the Xi, the officer at the pass, he wrote a five-thousand-word essay, the Classic on the Way and Virtue (Daodejing). The first part of the essay discusses the Way (Dao): “If the Way could be described in words, it would not be the eternal Way.” The second part of the essay talks about virtue: “One of superior virtue does not brag about his own virtue; thus he is truly virtuous.” This essay later became known as the Classic on the Way and Virtue (Daodejing). No one knows where Laozi went after he left the pass. Later generations revered him as the founder of Daoism.

Commentary:

In China, there was initially Daoism, then Confucianism, and finally Buddhism. Even though Buddhism was not transmitted to China from India until the very last, Daoism and Confucianism paved the way and served as the foundation for Buddhism. The founder of Daoism, Laozi, was actually the reincarnation of Mahakashypa, whereas Confucius was the transformation body of the Pure Youth Water-Moon. Because they had observed that the Chinese people would soon be ready to accept the Mahayana teachings, they made vows to be born in China to propagate Daoism and Confucianism in order to facilitate Buddhism’s transmission to the east. These three religions can be described by the following analogy: Confucianism is like elementary school, Daoism like middle school, and Buddhism like the university.

Laozi’s last name was Li. His first name was Er, and he was also known as Boyang and his posthumous title was Ran. He was born in the Ku County of the state of Chu during the Spring and Autumn Era. He worked as an imperial librarian (keeper of the archives) during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty and was a great philosopher who advocated unconditioned, effortless action and scorned conditioned actions. Unconditioned action does not mean one is like a wooden puppet or clay doll, which does nothing. It means: “one does nothing, yet everything is done.” One uses an unconditioned mind to do everything one ought to do. Upon accomplishment, one does not take credit for the work or become attached to what one has done. Absorbing conditioned actions into the unconditioned, he seems to do nothing yet has done everything. If one is attached to conditioned actions, such efforts can only be considered small actions, not great ones. Unconditioned action is the substance and source of conditioned action. It is most mysterious and wonderful.

Once, Confucius visited Laozi to discuss kindness and righteousness. Laozi said, “Seagulls are not white because they bathe everyday. Crows are not black because they are dyed that way everyday, either. They are white or black by nature, so you cannot say that white is better than black. Now you are using kindness and righteousness as a measure to discriminate good and evil. From the perspective of a person who understands the great Way, you are making a mistake similar to that of trying to differentiate whether black and white are good or bad.” After Confucius got back, he was silent for three days. His disciples could not help but ask him, “Teacher, when you visited the Elder Er, what teaching did you impart to him?” Confucius said, “I saw a dragon! This dragon transformed in a myriad ways in accord with yin and yang. I was simply flabbergasted and speechless; how could I possibly teach him?” Confucius believed that Laozi had obtained the Way of Nature, which has infinite transformations. To a person who has attained the Way, words are superfluous and unnecessary. If one is attached to defined and tangible principles, how could one hope to catch sight of even one claw or one scale of the dragon?

Therefore, Laozi advocated: “When people abandon the Great Dao, they choose to honor the teachings of kindness and righteousness. When intelligence prevails, hypocrisy appears. When there is disharmony in the family, filial piety and kindness appear. When chaos is rampant in a nation, loyal ministers emerge.” In the ancient era, the Three Emperors governed the world in accordance with the Way, and all the people were united. The Way was incorporated into the moral practices of daily life. Everyone did their share of work. Therefore, kindness and righteousness already existed although they were never explicitly mentioned. However, the rulers of later dynasties did not govern according to the Way, nor did they cultivate the virtuous example of unconditioned action. This gradually resulted in the decline of the Great Way. It was not the case that the Way had abandoned people. On the contrary, it was the people who had renounced the Great Way. Consequently, kindness and righteousness had to be established to educate and transform people’s minds.

After they were established, kindness could not prevail and righteousness could not be practiced widely without wisdom to guide and assist the teaching of kindness and righteousness. As a result, intelligence became predominant, causing the citizens to become more clever and deceitful. Gradually, simple and austere lifestyles disappeared; people became hypocritical and phony. Eventually, the country marched down the road of its demise; the danger of the Warring States and the Five Powerful Nations arose. During this period, so–called clever and ingenious gentlemen came forth. However, most of them were sham benefactors or righteous knights who used deceitful means to seek fame and advantages for themselves. All of these are the side effects and disadvantages of intellect.

When families are in disharmony, it is difficult for one to be filial to one’s parents or to be loving and kind to one’s siblings. If one could truly practice these virtues, they would spread throughout the world. For example, the father of Emperor Shun was blind, deaf and stubborn. Shun’s stepmother and stepbrother planned to kill him in order to snatch his wealth and property. Regardless, Shun was still very filial to his stepmother and kind to his stepbrother. These three people, in a way, helped Shun accomplish great filial piety.

When an emperor is muddled and the country is in chaos and danger, ordinary ministers and citizens only seek to protect themselves. Therefore, it is difficult for officials to preserve their dignity and integrity, or to practice loyalty and righteousness. If at this time, one can sacrifice oneself to repay the nation’s kindness by advocating righteousness and stabilizing the nation and the society, loyalty will naturally be evident without anyone having to explicitly promote it.

Concerning government, Laozi promoted the idea of having small states of solitary citizens. He said, “The people of neighboring states should be able to see each other and hear each other’s dogs and chickens; however, they never visit one another until they are old or about to die.” The citizens of each state lead simple and austere lifestyles. They are content with their surroundings, share the quiet living spaces and enjoy their own customs. They are neither given to high ambitions nor are they curious about new or strange things. They dislike moving afar, thus, carriages and ships are not of any use. Even though the people of neighboring states can see and hear each other, they do not exchange visits. Since they do not intervene in each other’s lives, there is no war. As a result, there is no place to house military forces or weapons.

The idea that people of neighboring states do not exchange visits does not mean these citizens just live in their own little world and peer at the sky from the bottom of a well—i.e. be narrow minded. It is a more highly evolved state of being. At this point, everyone puts forth their best effort, understands their own spiritual natures, and knows that everything comes from their own selves. Proper energy pervades heaven and earth. Their minds for the Way extend throughout the six directions (east, west, south, north, above and below). Their spirits can travel throughout space, arriving at any destination without physically having to travel there, reaching it promptly yet without having to hurry. They behold everything between heaven and earth as if it were in the palm of their hand. At this point, there is no boundary between heaven and the human realm. Being on earth is no different from being in heaven. Nevertheless, this highly evolved state must occur as the result of a natural progression. If one attempts to carry it out at the wrong time, chaos will occur. If humankind advances step by step, it will take at least a few hundred years to get started, and at least a thousand years to perfect this evolution. Thus Laozi’s proposition is very lofty.

Regarding education, Laozi advocated purifying the mind and diminishing desires. Starting by eliminating selfishness, then gradually reducing cravings, one can realize the goal of returning to one’s original divine nature.

Later, when the Eastern Zhou Dynasty was on a decline, Laozi rode a blue ox westwards through the Hangu Pass. The chief magistrate of the pass, Xi, invited him to leave some words of wisdom in written form, and what he wrote became known as the five-thousand-word Classic on the Way and Virtue (Daodejing). The first part of the essay discussed the Way: “If the Way could be spoken or described, it would not be the true, eternal Way.” The second part discussed virtue: “One of superior virtue does not brag about his own virtue; thus he is truly virtuous.” People of lofty virtue would never regard themselves as being virtuous; and that is the reason they have true virtue. The first and second parts together make the Classic on the Way and Virtue.

After Laozi passed through the Hangu Pass, no one saw him again or knew when he ended up. He could be considered the beginning of the Way and virtue. His spirit continues on, transforming all who hear of him, without beginning or end. He was truly a great person! Later generations honored him as the founder of Daoism.

To be continued

|