孝敬:德育之本

孝事父母,當願眾生;

善事於佛,護養一切。

(T279 華嚴經淨行品)

至今得道。現我父母。皆先世之緣。不由償債。父母世世放捨使我學道。累劫精進。今成得佛。皆是父母之恩。人欲學道。不可不精進孝順。一墮失人身,累劫難復。(T738 佛說分別經)

速證無上正真道,

其源莫非為孝德。

(T174 佛說菩薩睒子經)

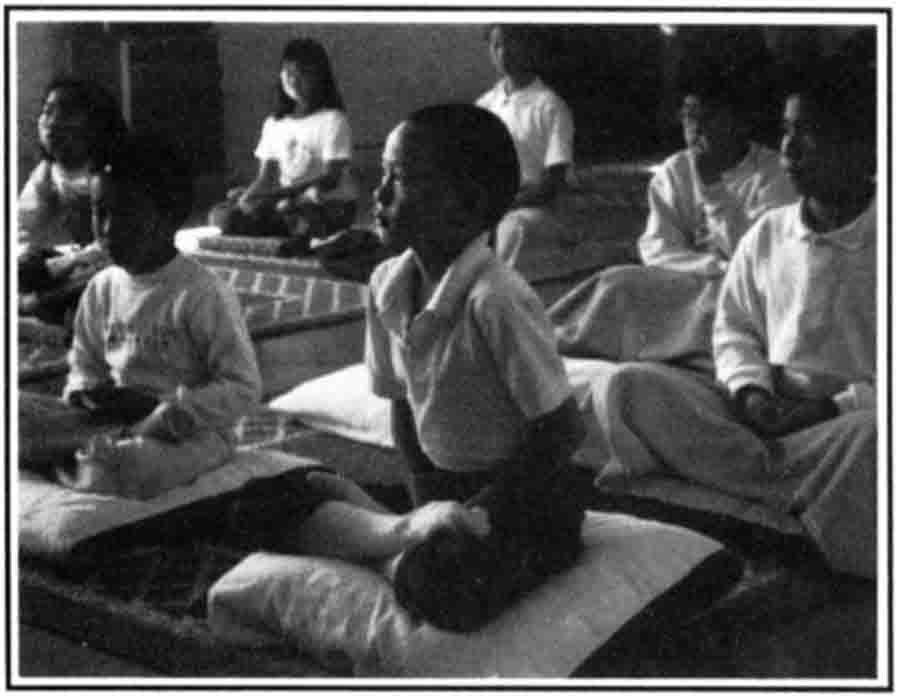

不僅在佛教中,在許多亞洲文明中,孝順已成為一種根深柢固的社會意識。從佛陀的本生故事懿範開始,多少世紀以來精進修道者盡孝的事跡已經成為印度、中國、東南亞的青年一盞導引正道的明燈。

中國對孝敬的啟蒙教育

流傳了兩千年,完整而有系統的中國文化已成為德育的豐富源泉。儒家倫常鼓鑄中國人的思維模式已歷千載,與之來往的國家,風俗皆受大影響。儒家經典是無數代文人所用的教材。此舉對於穩定與豐富華夏文明--世界上最偉大最悠久的文明之一--的價值是無法估量的。

海外華人將儒家道德弘播到他們所遷居之異國他鄉,啟迪當地的人的思想,使之受益。這種以德服人的和平文化傳播,乃古來孔孟所詮仁義道德之內涵。

在中國、朝鮮、日本與越南,幾個世紀以來,『孝經』、『三字經』、『四書』、與『弟子規』為青年學子們確立了道德情操的基礎。

這些教科書中,最早廣為流傳的是『孝經』。中國依傳統,從漢代(公元前 200 年至公元 200 年)以來,小學生要背誦孝經。『孝經』非常有系統地講如何盡孝,教導孩子如何要知報父母鞠養之恩。中國的傳統認為完美的道德是植根於孝道之上的。孝經所教之孝道,不是抽象的理論,而是日常生活之中至關重要的行為規則。孝道成為整個社會活動的經緯。它的應用面涵蓋生活的每一方面,萬德皆由孝德而化成。

孩子們通過『二十四孝』來加深他們對孝的認識。『二十四孝』所講的都是孝子們如何在極艱苦的環境下成就其孝之美名的。這樣的孝道教育極深地影響了中國人,許多人都如實將它應用到日常生活行為舉止中。” 『三字經』與『弟子規』包含具體的訓蒙與勸戒。告誡學子們當盡心盡職、謙卑和氣地孝事父母長輩。兩文均以三言一句格式而成,每一句都含有一個實際的道德教育主題,或是一個歷史故事,所教的或是一些啟蒙知識,或是過去的嘉行懿範。

香九齡,能溫席。

孝於親,當所執。

融四歲,能讓梨。

弟於長,宜先知。

另一本小學德育的入門書『弟子規』,包括了塑造孩童品行的大綱。

身有傷,貽親憂。

德有傷,貽親羞。

親愛我,孝何難。

親憎我,孝方賢。

這品行模式既不受文化限制,也不受時代約束。這些儒家典籍所述說的情形和教導的適用與應用範圍都極為普遍。由於孝順乃人類基本真情之一,根植於人的天性,因此無論於何種語言、何種環境之下,孝順都會激起良善的,震撼人心的反響。

以這些古人的啟蒙教材為基礎,佛教所興辦之教育必會經得起時間的考驗,並會像幾世紀以來亞洲的情形一樣,在西方有效地將德育傳授給廿一世紀的學生。

印度文獻中的孝道

在印度,那個撫育釋迦王子喬達摩‧悉達多的社會中,禮敬母親是一種基準的信仰。印度文獻聲稱,一位宗教師抵得上十位世俗教師;父親抵得上一百位宗教師;母親卻抵得上一百個父親。

Ramayana 中提到 Rama 王子的父親去世了,他一直等到守孝完成後,才接受大臣們的對他登基的請求。孝順父母是古代印度文化中不可分割的一部分。

幾個世紀之後,阿育王在他的第二篇Brahmagiri 公告中傳揚孝道:

「要善事父母和老師;要慈悲、誠實對待一切眾生,這些品德均須提倡。同樣地,持戒者應受到弟子的尊敬;倫常應善加維護。這是自古以來天經地義的法則,增福延壽由此而來,應善加遵守。」”

佛常以其往世之親身經歷來闡明法義。其中 Sonadanda Jataka 的故事稱頌母愛,Te-miya Jataka 的故事贊歎父母痛苦時子女所盡的孝行,在Sigalovada 經中更列舉了子女孝敬雙親,以及雙親關懷子女,雙方各自應盡的五項義務。因此佛陀在往昔所受的教育中,培植了他對孝道深深的敬仰,這對他的教化事業有著深遠的影響。

待續

|

萬德皆由孝德而化成。

The many virtues are nothing other than the manifestations of the one virtue, filiality. |

|

|

Filial Respect— The Basis of an Education in Virtue

“When I serve my friends with filial respect,

I vow that living beings,

Will serve the Buddhas with skill and care,

Protecting and nourishing all things.”10

“I have realized Buddhahood because of amassing merit and vigor, and because the parents in each of my successive rebirths allowed me to go forth from the home-life to pursue the Way. All of this is a reflection of my parents’ kindness. Therefore, those who pursue the Way must be vigorous when it comes to doing their filial duties. Because once they fall, and lose their human life, they will not be able to regain it in many aeons.”11

“The source of my rapid accomplishment of the Supreme, Proper, and True Tao was none other than the virtue of filial respect.”12

The lessons of filial piety are found tightly woven into the social fabric of many Asian civilizations, as well as in the Buddha’s teachings. Stories of filial paragons who were vigorous cultivators of the spiritual path, beginning with the lives of the Buddha himself, have been guiding young people along proper roads for centuries in India, China, and Southeast Asia.

Filial Respect in Chinese Primers

The teachings on virtue from Chinese culture, systematized and transmitted for twenty centuries, provide a rich source of moral lessons. Confucian ethics have molded the thinking of Chinese for thousands of years, and have influenced the customs of nations that contacted China. Confucian classics have provided educational materials for countless generations of Chinese literati. Their contribution to the stabilizing and enriching of one of the world’s greatest and longest-lived civilizations is inestimable. Confucian virtue, carried by Chinese emigrants around the globe, continues to enlighten and benefit the new societies it reaches. The vehicles for this peaceful “conquest by virtue and reason” are the ancient texts that transmit Confucius’s explanations of humaneness, righteousness, the Tao, and its virtues.

The Classic of Filial Piety, (孝經), The Three-character Classic (三字經), and Standards for Students (弟子規), as well as The Four Books (四書), have set the foundations in wholesome attitudes for schoolchildren in China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam for centuries.

The earliest of these textbooks to receive wide acceptance, the Classic of Filial Piety, was traditionally committed to memory by primary school students in China since the Han Dynasty (200 B.C. to the second century A.D..) The Classic presents a systematic approach to filial devotion and duty, introducing young minds to the need to repay the debt of kindness owed to parents for their sacrifices made while raising them to adulthood. Chinese tradition recognizes that the perfection of moral life is rooted in the virtue of filiality. Children are taught the principles of filiality in the Classic not as abstract theory, but as vital rules for daily human conduct. Filiality is the warp and woof of social intercourse, and its application covers all aspects of life. The many virtues are nothing other than the manifestations of the one virtue, filiality.

Traditionally, children expanded their knowledge of filial conduct by reading The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Respect (二十四孝), which illustrates the practice of filial piety under the most difficult circumstances. “Such education has deeply influenced the Chinese, and many actually applied the lessons to their conduct of life.”13

The Three Character Classic and Standards for Students contain concrete instructions and exhortations to devotion and humility towards one’s parents and elders. The lessons are written in three-word proverbs. Each bears a practical moral lesson, or a story from history, teaches a fact of life-science and common sense, or praises a model of exemplary conduct from the past:

“Little Xiang at nine years old,

Warmed the bed for his father.

Filial deeds for our parents,

Are what we all should do.”

“Rong was only four,

But could still give up the pears.

Respecting older brothers

Is the younger persons’ job.”14

Standards for Students is another elementary school primer containing guidelines for molding the character of children along the path of virtue:

“Whenever you injure your body,

Your parents feel grief and alarm.

Whenever you damage your virtue,

Your family’s good name comes to harm.

When parents love their children,

Obeying them is not hard.

To obey when parents are hateful

Takes the resolve of a noble heart.”15

These models of behavior are bound neither by culture nor time. The situations described and the knowledge conveyed by the Confucian textbooks is universal in scope and in application. Because filial devotion is a primary truth of the human condition, its lessons belong to a fund of “heritage learning”, that generates a wholesome and heart-felt response, regardless of the language or the milieu.16

A Buddhist-run educational program built around translations of these ancient primers will stand the test of time, and will communicate the lessons of virtue to twenty-first century schoolchildren in the West as effectively as it has in Asia for centuries.

Filial Respect in Indian Literature

In India, the society that fostered Siddhartha Gautama, the Prince of the Shakya Clan, worship of the Mother was a standard belief. Hindu scriptures state that one father is worth a hundred religious teachers, but one mother is worth a thousand fathers.17

The Ramayana relates that after the death of his father, the King, Prince Rama declined the ministers’ offer of succession to the throne until his prescribed period of mourning was over. Reverence for parents was integral to ancient Indian culture.

King Ashoka, centuries later, propagated the dharma of filial devotion in his second Brahmagiri Edict:

“Mother and father and teacher must be properly served. Compassion must be showered on all living beings. Truth must be spoken. These virtues must be promoted. Likewise the preceptor must be revered by the pupil. Relations should be properly treated. This is the ancient natural conduct. This makes for longevity of life. Therefore should this be followed.”18

The Buddha told stories of his past lives to illustrate his principles. Among them was the Sonadanda Jataka, that eulogizes a mother’s kindness. The Temiya Jataka praises care for one’s parents in distress, and the Sigalovada Sutra lists five duties approprite to children, in caring for their parents, as well as five duties parents should fulfill towards their children. Thus, the Buddha’s early education fostered a deep reverance for the virtue of filial piety, and it influenced his teachings profoundly.

To be continued

Notes:

10. T. 279, The Flower Adornment Sutra “Pure Conduct Chapter”.

11. T. 378, The Sutra of Differentiation.

12. T. 174. The Shyamaka-Jataka Sutra.

13. Sister Lelia Makra (trans.), Paul K.T. Sih (ed.), The Hsiao Ching, St. John’s University Press, New York, 1961, preface.

14. The Three Character Classic: Provisional translation in unpublished manuscript.

15. Standards for Students: Provisional translation in unpublished manuscript.

16. See Appendix I—to be published in a future issue.

17. Narada Thera, Parents and Children, Wisdom Series 38, p.2.

18. N.A. Nikam, Richard McKeon, eds., The Edicts of Ashoka, University of Chicago Press, Midway Reprints, Chicago, 1978, p. 43. |