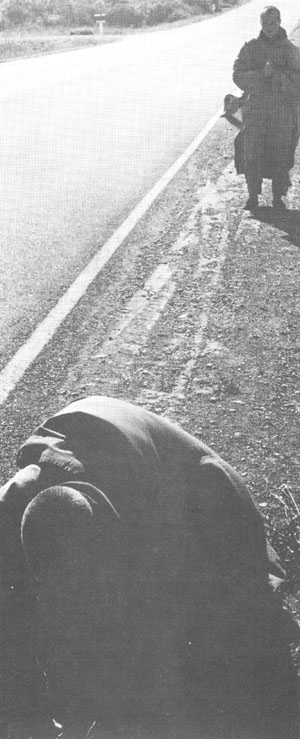

Bhikshu Heng Sure & Shramanera Heng Ch'au |

HENG SURE: May 16, 1977. It is hard to blend with the rhythm of this land because it has no rhythm. It is like a river of gas-fired metal on paved stone paths. No sound; one roar. No smell; one stink. No light; one haze. No time; pure morning when the zero is pure and then the one comes into being and the two and the three and the millions. No human can live here. We have made a hostile environment at great cost. The World Trade Center runs on electrical power, is adorned and sanitized costing millions of dollars for the few hundreds of people who will ever see it and the millions of ghetto Chicanos who will never see it or dream of it. It is like Versailles. It is a thin reality, disposable, ready to be abandoned. Dead. With Muzak. We come in off the street to relieve ourselves and return to our lively hells of streaming metal. "Do you believe that praying and bowing can affect disasters and catastrophes?" Yes, we do, don't you? Where do disasters come from? They come from the accumulated heaps of bad karma that you and he and I pile up and after a while the scale is unbalanced and nature, erupts or a plane crashes and human suffering results. But it starts with us first; we make our fate with every present action we do, with every thought. So by working directly with the mind and by concentrating a prayer for no harm, no hatred, no weapons, no suffering, we are seeking a response right at the source of the problem—our own minds. Do you see the link? Yesterday and this morning I experienced a shrinking of desire to this point: I recognized that I was not looking forward to today with any pleasure in mind. I did not have any expectations of pleasant, pleasing, or positive events. At the same time I was not hoping to avoid any unpleasant events--those come as part of the work we do. |