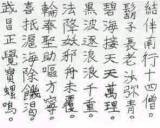

The Vomit VerseBy

VENERABLE MASTER AN TZ'U TRAVELLING BY BOAT FROM T'IEN CHIN TO HU PEI DURING THE AUTUMN OF THE THIRTY-FIFTH YEAR OF THE REPUBLIC AND ALMOST ENCOUNTERING DISASTER BY CAPSIZING. ON RECEIVING A RESPONSE THERE WAS MADE THIS VOMIT VERSE. THE

SANGHA, FOURTEEN IN ALL, SAILED SOUTH- This event took place during the autumn of the thirty-fifth year of the republic (1946). I had been living at the Ta Pei Yuan in T'ien Chin. Old Dharma Master T'an Hsu was explaining the SURANGAMA SUTRA there and I wished to see him and Dharma Master Ting Hsi. At that time Ting Hsi' s name was Ju Kuang ; it was not until after the defeat of the Japanese that he changed it to Ting Hsi. I wished to meet them, but it is not very easy to meet an old Dharma master. First you have to go to the guest hall and inform the guest prefect who makes an appointment for you. Of course, if the master does not wish to see you, you may have to wait several days and still never have a chance to meet him. What was my aim in seeing them? It was to draw near to a good knowing advisor. Master T'an Hsii was a very famous Good Knowing Advisor from the Northeast. At that time I was just a sramanera and wished to bow to these two good knowing advisors. I waited for several days and yet still did not have the chance to meet them. One day Dharma Master Ju Kuang was returning to the Northeast. He left early in the morning, and I waited in the courtyard in order to have a few words with him. When he appeared I bowed and told him that I was from the Northeast, my name. and that I was planning on going to P'u T'o Mountain to receive the precepts. He said, "Whatever difficulties you have take them up with the Abbot. I don't pay any attention to such affairs!" He thought that I wanted to beg money from him. At that time I actually did not have any money, but be that as it may, I certainly was not out to beg. I said, "You're mistaken. I'm not out to beg from you." "Oh," he replied, "Then there's even less of a problem!." and left. After that I saw Dharma Master T'i Ching, the Long-Beard Elder. Bhiksu Chih Hai, who was here yesterday, was at that time called Mo Ju and was one of the fourteen of -us. There was another among us whose body always stunk. When he stood in a room no one else could stand it, so great were his spiritual penetration's. Such a stink comes from not maintaining precepts. If one holds precepts his body will give off a sweet smell. There were also T'i Ching, Sheng Chao, Sheng Miao, Yung Ling and Ching Chieh. Sheng Chao, Sheng Miao, ching Chieh, and I were all sramaneras, the rest. Pen Chih, Ying Hsiu, Mo Ju, Hui Ju. Chiao Chih, YenHsTu, Jen Hui. and Chao Ting. were bhiksus, and so it says. The Sangha, fourteen in all. sailed south, Now, I'm not trying to build myself up, but these people simply did not understand the first thing about traveling. When we had to get shots and papers, they did not have any idea what to do, and I had to take them all around and arrange things. Even T'i Ching did not know what to do; their brains were old and dull. No matter what, however, there were able to put on an appearance. We went to get our shots and, of course, it's always bhiksus first, but since they had no idea how to go about it, they put me up front again. Even T'i Ching did not know how to handle this affair. Ah!! Chinese people who have left home are too pitiful, unable to do so simple an affair. After I took them through customs and inoculations and so forth we finally boarded the boat. I don't recall what it was called. Ten bhiksus, and four sramaneras boarded, altogether a party of fourteen. Long-bearded Elder, sramapera green. T'i Ching had a very long beard and was an elder, and so in this poem I called him Long-bearded Elder. There are many ways to explain this name. First you could say that his beard was long and his years were many, he was over 60. He was an Old Dharma Master, the oldest among us. The second explanation is that he was extremely severe; he liked to scold people more than anything. As soon as he saw anyone he would shut his eyes and bellow, "You La La La!" That's what he said. La La La. There is yet a third meaning. In the Northeast there is an expression, "Redbeard", which means to wear a false face, often made of paper, leather, or some such substance, with a long red beard attached to it. Whoever wears such a mask can go around and commit robbery and no one can see who he is. So, another name for a bandit is "Redbeard". Why did I give him this name? Because when I came from the Northeast I had a little money with me, but he made me give it all to him since sramanera are not allowed to carry money. He was really stern. No matter how much money one had, one had to give it to him on this trip. This is just like robbery and so I called him Long-bearded Elder. The

azure sea reached the sky—sky for ten thousand miles. When

we boarded the boat, all that could be seen was sea and sky; the two met

and nothing else was visible. It was as if one could see very clearly

for ten thousand miles into the distant sky. Black

waves followed billowing--wave upon wave a thousand fold.

In the beginning it was an azure sea, but after travelling we

encountered a black sea, blacker than ink.

Black waves arose, not just one or two, but wave after wave,

waves a thousand fold.

Oh! Lots

and lots of waves!

The boat, which was about three hundred feet long, was pitched

about on the sea.

One end would rise up about fifty or sixty feet and then plunge

the same distance.

All you could do was lay down; it was impossible to even stand.

It was really extreme. Dharma subdued the monsters, the boat was not capsized. Originally this crossing was easy—never like this. Generally it was about a one week trip, but this time it took over twice that time, since the boat made no progress in the black sea, but was just tossed about. This was because there were many sea monsters stirring up the water in an effort to drown me. Why was this? Back in Manchuria I had had a dharma battle with them. We fought for a week and eventually I won. Then, many of these strange monsters who lived in the water—oh I don't know how many—wanted to overturn the boat and drown me. You do not believe this simply because you have never met up with it, you have not encountered such fierce things. There were, however, certain methods, a certain number of dharmas, which were understood and used to subdue the monsters. Consequently, the boat was not capsized. The wheel received the sage's aid and vomiting was quelled. The wheel, you could say, means the steamship (lit. wheel boat). Because Buddhas and Bodhisattvas secretly helped out, the boat was not turned over. You could say that my Dharma protecting Bodhisattvas were helping out, and for this reason the boat did not overturn. But it was still very fierce. No matter what one ate on this passage, he could not eat his fill. Why not? Originally we had planned to make the crossing in one week; from T'ien Chin to Shang Hai was always a week's trip. This time two, or almost three weeks were required and still we had not made port. The food therefore, had to be rationed. Most of the monks on the trip did not eat after noon, and so they had to eat even more in one sitting. Since they were unable to get their fill, they were very uncomfortable. For the first three days everyone ate his fill but after the fourth day, when it became clear that we would not reach Shang Hai as soon as expected, everyone had to eat less. This was particularly true of the monks who had not given much money for fare and were travelling cheap class. If you do not give any money and people do not give you food, you have no recourse. At that time everyone was hungry. One

of the party, Yung Ling, tried to defame me before Old Long-bearded T'i

who said to him, "You La La La, just talk about being hungry all

the time. Just take a look at

Dharma Master An Tz'u, he just eats one meal a day and does not complain

like you about hunger." Yung

Ling said,"UH! Of course he

doesn't talk about hunger. He is

eating on the sly." "You

La La La," said Old Long-bearded T'i, "What is he stealing to

eat?" Yung Ling said,

"He steals rice crust." (the crisp layer of rice left on the

inside of the pan when rice is cooked in a Chinese style pan.

It is considered a bit of a treat although it is an awful lot

like Rice Krispies. I don't think

it makes quite as much noise, however—Translator's note.) Why

did he say this? It is not

surprising. Sometimes we went up

on deck to take some air; One day I was there near the gaily and the

cook brought out a small piece of rice crust and gave it to me.

Yung Ling walked by, saw this, and laughed slightingly. Well, I had accepted the food, since it had been given to me, but

immediately afterwards gave it to the little Sramanera Sheng Miao. He,

young child, ate it. I did

not eat any of it at all, Yung

Ling, seeing this, said that I had eaten it. So

it was that for almost two weeks on the boat everyone ate only half

full. Now, I don't care, half

full, or even a week or two or three without eating, is no problem for

me, but these long-bearded elders, long bearded bhiksus could not take

it, and said I was stealing food. Anyway, no matter what you ate, it was puked right back up with bitter stomach fluids. Reaching Hu Hai hunger and thirst dispelled. When it became totally unbearable, we reached Shanghai. Hu is another name for Shang Hai, Then the Long bearded Elder said, "Buy Noodles." Since they were so hungry, they got a couple of boxes. There had also not been much water aboard the ship and as soon as fresh provisions were taken aboard Long-bearded T'i washed his face again and again and again. Since there had barely been enough water for drinking there was, of course, none left to wash with, and one certainly could not use sea water since it is so salty. In all he probably washed some twenty times that day. It was really laughable. They bought the noodles and cooked them up. Since they were so hungry they made a lot. Basically I do not eat in the morning, but they had made so much that they couldn't eat it all and were about to dump the leftovers into the sea. I saw Yung Ling, who is still in Hong Kong, who said to me, "Do you want some?" I said, "Since you don't want it, okay." I agreed and took two bowls of noodle soup. Yung Ling then went to T'i Ching and said, "He claims not to eat. When you're looking he does not eat, but when you're not looking he'll eat anything." How do I know he said this? First of all I know what kind of person he is, and secondly. Long-bearded T'i asked me about the noodle soup and the rice crust. He said, "How could you eat the soup? You said you do not eat in the morning, and then you went ahead and ate!!!" He really chewed me out, and so it says, "Reaching Hu Hai, hunger and thirst dispelled." At Wu Tsanq. Right Enlightenment, the sound of the jeweled conch.Wu Tsang is another name for Hu Pei Province. Right Enlightenment is the name of the temple there where I lived. While I was there I lived on a meditation cushion near the door. I had no sleeping bag or anything else, and wore the same clothes day and night. Everyone said, "How come you're not cold?" I answered, "Who is cold?" I played really stupid for them and when they asked if I was cold just replied, "Who is cold?" Afterwards many said, "Ah! Your bitter practices are a thing we could never bear." Since one of these fourteen came by here yesterday I remembered this poem for you. Otherwise I'd have forgotten it.

|

|

|

|

|

A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF THE HONORABLE BHIKSU CHIH HAIDharma Master Chih Hai, a native of Hopei, left home under Venerable Master Yueh Ch'en in 1943 at Tzu Fu Temple, Hung Lou Mountain, Huai Lai County, China. Later he received the complete precepts at Kuang Chi Temple from Precept Master Hsien T'sung " followed by study at the Kuang-Hua Buddhist Academy in Peking, and travel throughout China. In 1948 he left Mainland China for Hong Kong, where he entered the South China Buddhist Academy to study the teachings and practices of the T'ien T'ai School. In 1950 he traveled to Burma and lived at the Ho P'ing Pagoda for eight months. Upon his return to Hong Kong he entered Nei-Ming Buddhist Academy. In the winter of 1967 he took up residence in the United States. |

|

|

|

|

|

On October llth, Mrs. Else E. Richards, the grandmother of Dharma Master Heng Shou, visited the Buddhist Lecture Hall along with over 30 friends from Bakersfield, California. She arrived early Saturday afternoon to talk with her grandson. The following is part of her conversation with the Venerable Master Hua. Master: "What do you think of your grandson's leaving home?" Mrs. Richards: "He's found his right place." Master: "You have deep conditions with the Buddhadharma.' Mrs. Richards: "That's not at all unlikely." Master: "Whether or not it's actually that way, I don't know." Mrs. Richards: "You get an extra bow for that." Master: "Why?" Mrs. Richards; "If one speaks otherwise, he is already dead." Master: "I've been dead for some time." Mrs. Richards: "That's no worry, there is no death." Master:

"You haven't forgotten your wisdom." Mrs. Richards: "If I have any." Later that evening the fourfold assembly and guests gathered to hear Dharma spoken by Dharma Master Heng Shou.

|

|

|

|

|