|

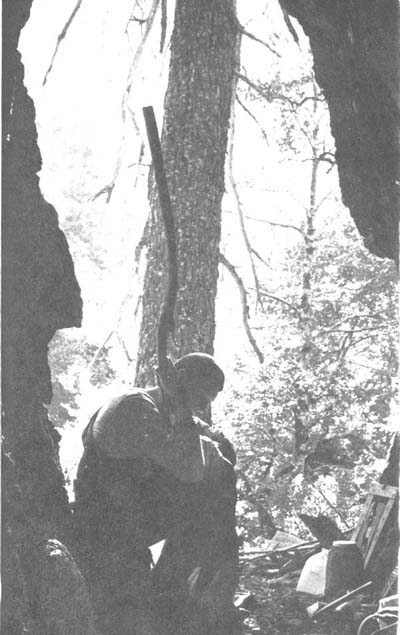

Heng Kung has vowed to spend one month out

of every year in the wilderness, in order to "always be mindful of the

yogic ideal of renunciation," he said last week upon his return to Gold

Mountain Monastery in San Francisco, where he lives with other American Buddhist

monks and laymen.

It was Heng Kung who happened upon the

cave he chose for his month of isolation this year. The cave had been hewn by

earlier miners’ 20 feet deep into the face of a rock wall at the bottom of a

cliff.

The walls glittered with minerals, and at

the back of the cave was a cup-shaped recess, still showing traces of the silver

that had been mined there. "It just looked like some monk should be sitting

there spending his life in single-minded concentration," Heng Kung said

afterwards.

The

neighboring woodsman and landowner, whose cabin a few miles distant was the

nearest habitation, had some doubts about the monk's spartan diet. People have

to eat meat if they're going to have enough energy, the woodsman believed.

Vegetarianism is a basic principle of Buddhism, which forbids all forms of

killing.

On Heng Kung's first day in the mountains,

the woodsman suggested that they walk along the nearby river to-an isolated

orchard to-gather and eat their lunch. The monk assented-and was surprised to

find that the orchard was a five-mile walk from the road. When the two men

reached the orchard, after making a detour to climb a mountain, Heng Kung found

nothing to eat: the apples and pears were not ripe, while the figs were

inedible. The woodsman then suggested that they walk to his cabin to

eat--another five miles uphill. As his companion: struck off at a brisk pace,

Heng Kung's suspicion was confirmed that the entire expedition was the woodsman,

effort to prove his idea that a vegetarian diet is inadequate.

They walked through the hills till

nightfall, but Heng Kung forced himself to keep) a fast pace and even toot: the

lead, although he had eaten nothing all day.

That won the woodsman's respect and he

came daily to the monk's cave for lessons in meditation—which he admitted, was

more difficult even than walking all day in the mountains. At the end of the

month, he gave the monk a tall wooden walking-staff he had carved as a token of

his admiration.

Rejection of the ordinary life of striving

for affluence and worldly success is not new to this young American. Before he

took the vows of a Buddhist monk at his San Francisco monastery, Heng Kung spent

several years in meditation in the mountains of Nepal and South India.

Difficult as it is, the renunciation he

practices is not meant as a form of self-deprivation. Rather, Heng Kung sees it

as a method of achieving unshakable peace of mind, and of living in harmony with

other people and with surroundings, no matter how adverse they might prove to

be.

"When people are desirous of worldly

objects, they create obstructions and they get involved in doubt and

trouble," he says.

|